Fireburn: The Uprising of 1878

After the abolition of slavery in 1848 a new labour bill [Arbejdsregulativet] was passed in 1849 to regulate the conditions of the now free workers. The law stipulated a day wage and ruled that workers could only change jobs once a year, on October 1st.

After 1848 the former slaves worked on the same plantations as before, and their living conditions did not improve much in terms of accommodation, healthcare, education or income. During slavery the plantation owner had a duty to provide for the old and disabled, but he did not have the same obligations to allegedly free workers. The same was true of healthcare. Before 1848 the slave owner had paid for the workers on his plantation to visit a doctor, whereas after 1848 these costs had to be covered by the now unenslaved workers. Their pay, however, was so low that it was almost impossible to provide for themselves and their families, let alone pay for medical care.

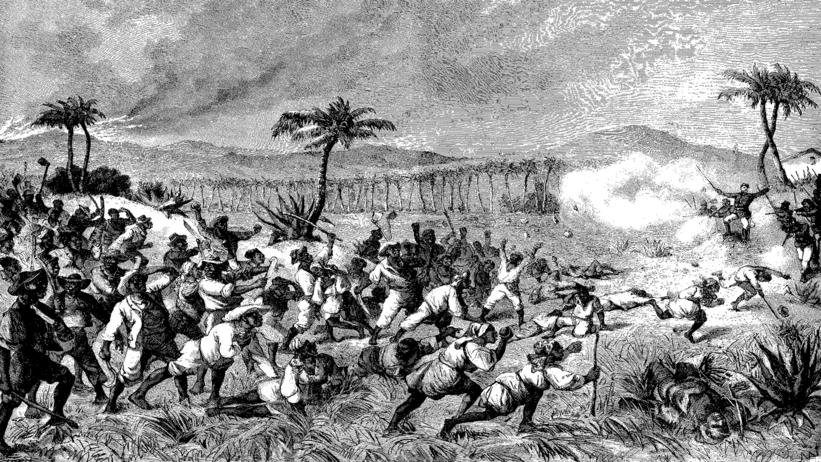

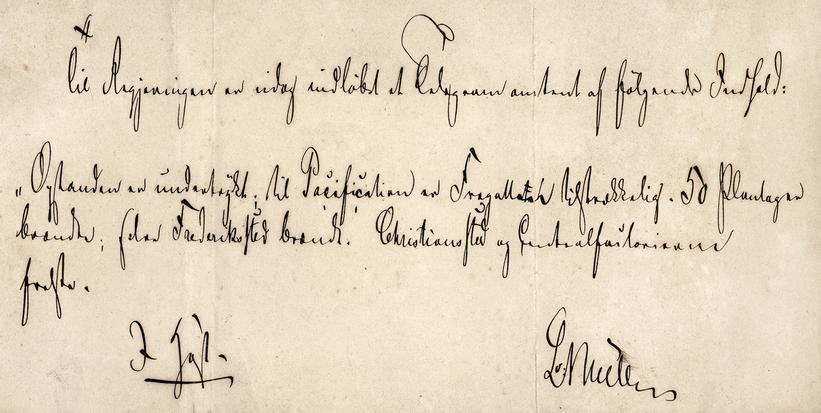

This led to increasing unrest. On October 1st 1878 – job-change day – many of the workers on St. Croix’ were gathered in Frederiksted, where there were celebrations and drinking. After some commotion on the streets the police launched a brutal clamp down, sending a farm labourer called Henry Trotman to hospital. The unrest continued, and rumours spread that Henry Trotman had died as a result of police brutality. After this the riot escalated. Trotman was not dead, but the police and military had to retreat to the fort in Frederiksted to escape the angry masses. The workers starting to charge the fort, but were unable to penetrate its defences. A horseman was despatched to the town of Christiansted at the other end of St. Croix to alert the colonial powers and request assistance. Late that night buildings in Frederiksted were set on fire and shops were looted.

The next morning soldiers from Christiansted came to rescue the fort, but the torching of fields and plantation property on St. Croix continued throughout the day. Around 50 plantations and most of Frederiksted were destroyed by fire, which is what gave the revolt its name: Fireburn.

The Three Queens

Today three women who participated in the rebellion have gone down in history as a symbol of resistance to colonial power in the West Indies. The women are known as Queen Mary, Queen Agnes and Queen Mathilda. All three of them were arrested together with a fourth woman called Susanna Abrahamson / Bottom Belly, and served part of their sentence in the Christianhavn women’s prison in Copenhagen in the 1880s.

After the rebellion there were slight improvements in the labourers’ conditions, including higher pay. Their battle for reasonable working conditions under Danish rule did not end here, but continued until the Danish West Indies was handed over to the U.S. on March 31st 1917: Transfer Day.