The Danish Expedition

The Excavations

In 1930 the young Danish archaeologist, Harald Ingholt, travelled to the town of Hama, on the Orontes River in Western Syria, in order to dig some test trenches on the mound. Since these trenches proved promising, Ingholt was allowed to conduct full-scale excavations in the years from 1931 to 1938, with the support of the Carlsberg Foundation.

Although archaeologists had been working in Syria for some time already, it may be said that the Danish excavations at Hama played an especially important role in illuminating the history of the western part of the country, most significantly in the earlier periods. The objects from the excavation that were shipped to Denmark also came to play an important role in the collection of the Antiquities Department in the National Museum.

The Various Tasks on the Excavation

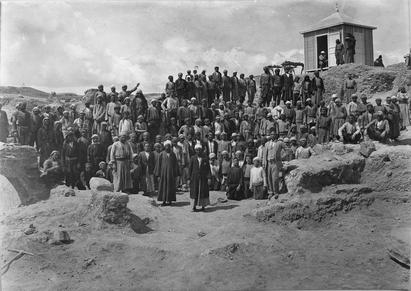

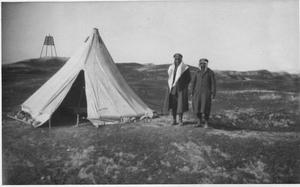

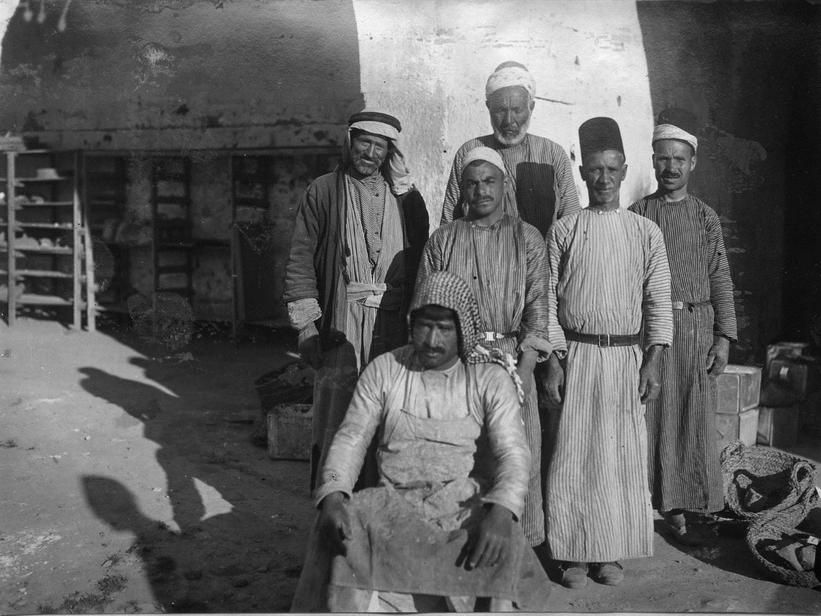

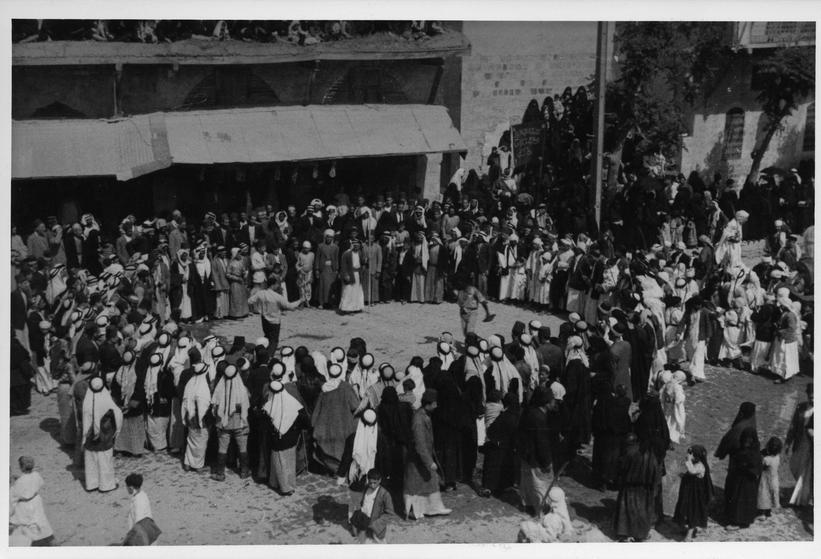

Ingholt hired local men to do the actual excavating. The workers came from Hama and local villages in the Orontes Valley. The workforce could be made up of as many as 400 people. There was strong competition for jobs on the excavation because the pay was better than that of local jobs in both the public and private sectors. Supervision of the workers was undertaken by Ala ad-din afandi, a member of the powerful al-Kilani familiy in Hama. Egyptian foremen, who had been trained in the Megiddo excavations in Palestine (now Israel) or the excavations of the famous British archaeologist Sir Flinders Petrie, supervised the more precise excavation work.

The Danish archaeologists supervised the overall excavations in general, and recorded the daily results in their notebooks. They also registered all the finds, which meant making a list and a description of each object collected from the excavation. Architects measured and drew all of the buildings and other architectural elements uncovered in the various time periods. Artists drew the pottery and other small finds, and photographers documented these, as well as the excavation layers as they were uncovered and the architecture and other special features. Conservators were responsible for preserving and restoring objects. Because pottery plays such an important role in understanding the chronological and cultural divisions of an excavation, special attention was paid to washing them, and restoring them when possible, and recording them in drawings and photographs.

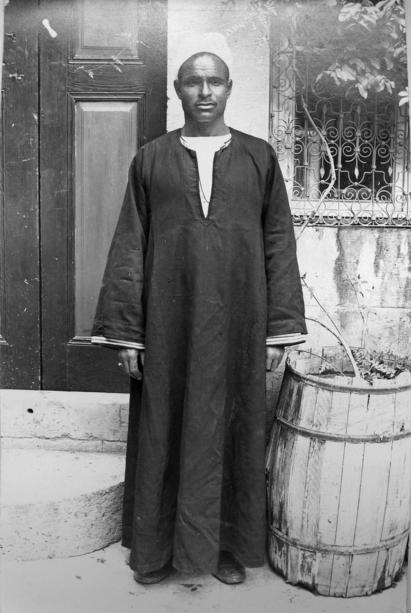

Servants, a cook and a laundress were employed in the dig house. The chief servant, Said ibn Muhammad al-Tabba, taught the expedition members about local society and customs, as well as some Arabic. Subhi, the cook, was especially appreciated. The diet consisted of seasonal fruits and vegetables, lamb from the local fat-tailed sheep, as well as yoghurt, along with the traditional unleavened bread, unsalted butter and goat’s cheese. If one wanted finer fare, it had to be imported from Beirut.

Work and Leisure

The workday began very early, when it was coolest, and a siesta was taken midday, when the sun was hottest. At night the expedition members could read the 3-week old newspapers they received (in the first year by the light of candles or lanterns, before electricity was introduced). It could get cold at night, so a glass of cognac was often had before retiring early to bed.

All the expedition members and the local workforce had a free day on Sunday. Usually trips were organized for this day, often on horseback.

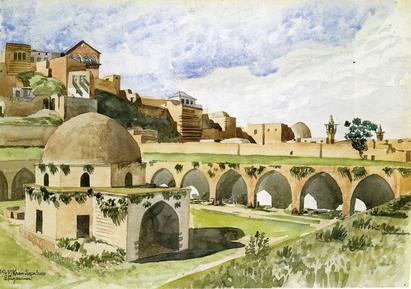

The architect, Ejnar Fugmann, also used his Sundays to pain watercolours of the charming old town of Hama. Sometimes there were local celebrations, which the archaeologists could attend and photograph.

The expedition also received visitors from near and far. Among the visiting dignitaries were many famous archaeologists, including Sir Leonard Woolley, who had been excavating the so-called Royal Tombs at Ur, in Southern Iraq (Mesopotamia). Max Mallowan, who excavated many important sites in Iraq and Syria, also visited the excavations at Hama, along with his more famous wife, Agatha Christie.

Living Quarters

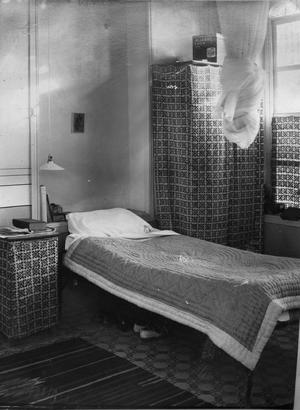

In the beginning, the expedition was housed in a school. Soon, accommodations were found in a fine old traditional house. The second floor of this house was divided up between a male section (called a salamlik – a public reception area), used during the daytime as common rooms, and a female section (haramlik – the private area), used as sleeping rooms. The haramlik faced north, so it was quite comfortable in the heat of the day, but cold in wintertime. The water supply for this building came via an aqueduct connected to one of the famous water wheels along the Orontes River. At the house, the water was led to a fountain in the courtyard, as well as to the latrine near the kitchen. Because the water from the river was not suitable for drinking, it had to be filtered in large clay vessels and boiled before it was used. Heat at night was provided by portable coal braziers, which in fact offered little heat. When there was time, expedition members could enjoy the beautiful view from the balcony.

After 1935, the expedition was able to move to a caravansary, a traveler’s inn. This building, Khan Rustam Pasha, had been built in 1561 by the Grand Vizir Rustam Pasha during the reign of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, and was recognized as one of the most beautiful Turkish Ottoman Period buildings in Hama.

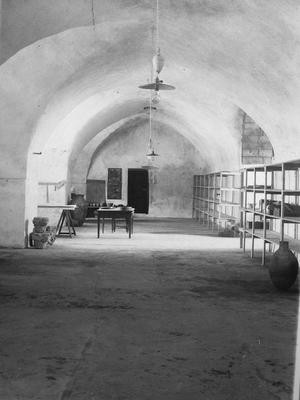

Khan Rustam Pasha was a structure enclosing a large courtyard. In the middle of the courtyard was a small mosque. Opening on to the courtyard were the vaulted rooms that once housed travelers and their pack animals. These were now used as bedrooms, workrooms, laboratories, a dark room for the photographer, the kitchen and the dining room. There was also plenty of room for storage of the archaeological finds from the excavation.

Members of the Expedition

Harald Ingholt directed the excavations for the duration of the project, while the makeup of his international team changed over the years.

- Archaeologists

Victor Chistian, Florence Day, Poul Jørgen Riis, Nora Scott, and Vagn Poulsen. - Architects

Charles Christensen, Ejnar Fugmann, Jørgen Rohweder, and Georg Tchalenko. - Conservators, photographers, etc.

Mathilius Schack Elo, Bodil Hornemann, and Frode Jensen.

Other participants included F. Comstock, Poul Dueholm, E. Esmer, Marc Le Berre, Elias B. Marsh jr. and I. Terentieff.

You can learn more about the participants in the section Members of the Expedition.