Written sources shed light on Viking travels

The Vikings did not write books themselves. We nevertheless know about their movements in the world, because foreign chroniclers and writers described their encounters with the Vikings.

We can read about diplomatic and political exchanges, as well as the plundering of towns, monasteries and royal estates. We also learn about their participation in various conflicts as “mercenaries” and their collection of taxes on the Continent. There was also long distance trade and missionary activity. In other words, the sources reveal the foreign politics of the past.

It is also a picture that can be confirmed when the archaeological evidence is examined, including objects left behind by the Vikings, which we sometimes find today.

What do the written sources tell us?

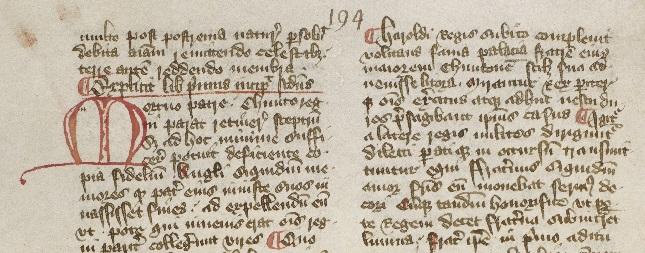

The written sources that tell us about Viking activities in Europe should be viewed with caution. These were written with the events seen from one side, from a particular viewpoint, and typically with a specific political purpose in mind. There are various records of the Scandinavian Vikings’ expeditions and travels to West European countries. Apart from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, another important source is the Royal Frankish Annals. These were written from 780 AD onwards. They describe the period from 741 to 829 AD, in other words the beginning of the Viking Age.

Many of the written sources mention plundering and attacks. For example, written records tell us that the Vikings attacked the south-east coast of England as early as 787 AD. They also carried out violent raids in various parts of Europe from the first half of the 9th century. These included the attacks in France, upon Toulouse in 844 and Paris the year after.

However, we can read about more than just violence and raids in the written sources. Various European monastic chronicles and royal annals reveal other information. They include descriptions of contacts between diplomats from the Frankish court and the Danish kings. We also read that gifts were exchanged.

These diplomatic contacts were cultivated so that prisoners could be exchanged and young Scandinavians could receive an education at the Frankish court. The European emperors, especially Louis the Pious, regularly interfered in the various Danish power struggles and succession disputes, and attempted to influence the development of Scandinavia. This reached a peak when the Danish king Harald Klak visited Ingelheim/Mainz in 826, where he was baptised and received precious baptismal gifts.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

"In this year came dreadful forewarnings over the land of Northumbria, terrifying the people most woefully: these were immense sheets of lightning and whirlwinds, and fiery dragons were seen flying through the sky. A great famine soon followed these signs and not long after in the same year, on the sixth day before the ides of January, the harrowing inroads of heathen men destroyed the church of God in Lindisfarne by robbery and slaughter.”

The year was 793 AD. This is an account of how the Vikings plundered and laid waste to a monastery on the island of Lindisfarne, off the north-east coast of England. It was written down in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which is one of the most important sources about the history of England during the Viking period. The core of the chronicle was written down in Wessex at the end of the 800s, but the writing of it continued at other locations in England in the following centuries.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle includes descriptions of the Vikings and their activities in the English and Irish areas. Or to be more precise, these descriptions tell us the way in which the inhabitants of the British Isles viewed the Vikings and how they wished to pass on the stories about them to future generations.