What makes Tranquebar a Place?

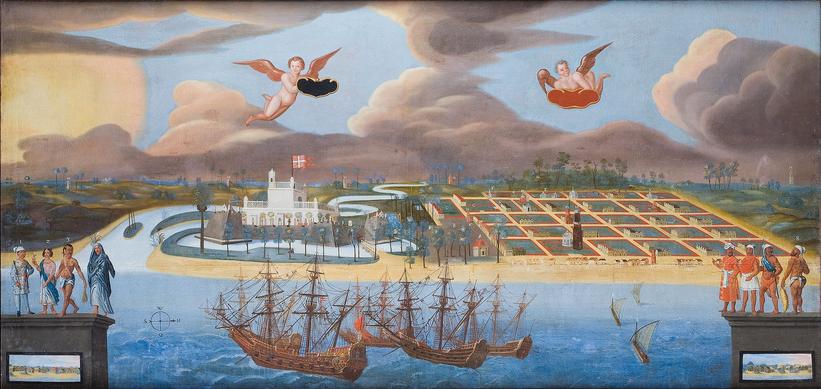

Tranquebar or Tharangampadi is a place not only in India but also in the world. It has carved out its own significant space in history through the many different kinds of human activities at that particular spot, from ancient times up until today.

People dwell there for longer or shorter periods of their lives, as husbands or wives brought in from other villages, or as merchants, school teachers or pupils from nearby towns, currently living in the boarding schools or the teacher training centre. Some also come as national or international tourists to visit Tranquebar for a day or two, or they arrive as national or international NGO staff members, stationed there for a limited time in order to do social work or to renovate old buildings, vernacular as well as colonial, as a part of Tranquebar’s current cultural heritage revival. And they come on national holidays and hot days, when they travel from the hinterland to the Tranquebar coast in order to enjoy the coolness of the sea. Others come to visit the old Shiva temple, Masilamani Nathar, as worshippers or simply to have their wedding photos taken in front of this picturesque, albeit partly collapsed, temple, lashed by the waves; or they may arrive as Christian pilgrims to the Jerusalem Church, the mother church of all Lutheran Protestants of Asia; or in the past, when they disembarked from the large sailing ships anchored at the roadstead off Tranquebar and were taken through the heavy surf in smaller boats rowed by locals, stepping ashore to serve as soldiers, colonial civil servants or Christian missionaries, sent from distant places such as Denmark, Island, Norway, Germany or England. Or when, as distinguished envoys and representatives of the Nayak or Raja in Thanjavur, they turned up on elephants in pomp and circumstance to collect the yearly tribute from the Danish colonial governor. Or when they entered the village as religious heads of Shiva temples and were received by processions of musicians and local temple dancers.

People have, over the years, however, not only come to this place known as Tranquebar. Some have also left the place to be married and to live in other villages; or they have temporarily departed on business trips or migrated to work in Ceylon (later Sri Lanka) or to other parts of India and abroad, recently often to Saudi Arabia, Malaysia or Singapore.

These very different kinds of movements, in and out of the place, throughout history, are what make Tranquebar an interesting place to study. They testify to the fact that Tranquebar is connected to the wider world in various ways. As a place, the experiences Tranquebar affords are not only for those who have spent longer or shorter periods of their lives there, today or over the centuries. The experiences and imaginations it affords are also for people in other parts of the world who perhaps received letters or reports from sisters, brothers, envoys, missionaries or other people stationed there, or who consumed the exported products such as spices and textiles, which may have altered not only their cooking habits but also their means of furnishing their beds. These distant consumers started to demand pepper in their food or cotton linen on their beds, that is, linen coloured with indigo and imported from India, just like the coveted pepper.

Indeed, there would be no place at this location were it not for all the activities in which its inhabitants have engaged and all the movements of people, ideas and items across borders. This has produced tracks and routes internal to Tranquebar, in addition to tracks and routes between it and other places. The cross-cultural marks stamped on these tracks and routes by the coming, going and staying bring these together into a single field of inquiry for this book.

In the above sense, the place called Tranquebar constitutes a topic rather than a natural object. From the perspectives of a diverse range of academic disciplines, social anthropology, art history, sociology of religion, ethnography and history, the chapters of this book will examine people grappling across cultural borders, along routes and tracks related to this particular place in South India.

Fihl, Esther. (2014). “Introduction: What makes Tranquebar a Place?”, in Esther Fihl and A. R. Venkatachalapathy (eds.), Beyond Tranquebar: Grappling across Cultural Borders in South India. Orient Blackswan.