The Danish Archaeologist Gudmund Hatt

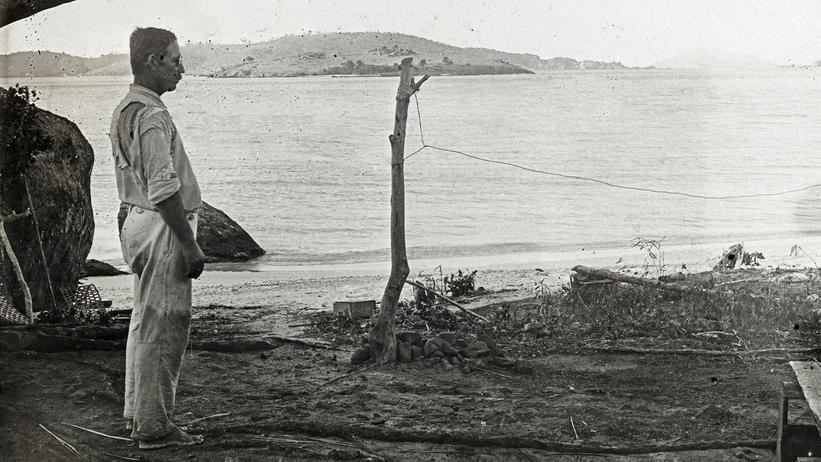

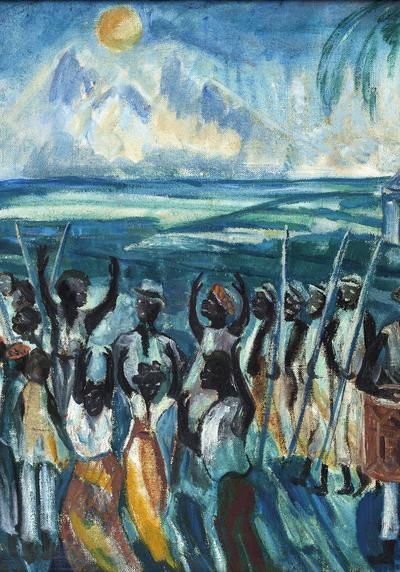

The Danish archaeologist Gudmund Hatt, his wife the artist Emilie Demant Hatt, and the Dutch anthropologist J.P.B. de Josselin de Jong embarked on an expedition to the former Danish West Indies and the Dominican Republic. The goal of the expedition was to learn more about the indigenous people of the Caribbean who had inhabited the islands prior to European colonisation. During the nine months of the expedition they excavated no less than 30 sites, including the indigenous settlement near Salt River Bay on St. Croix, Columbus’ destination on his second voyage in 1493. Archaeologists classify these international finds as ‘pre-Columbian’, since they originate from the time before the arrival of Columbus.

30 excavations

The large number of excavations was only possible due to the help of locals, who told the Hatts where to dig. On St. Croix the plantation owner and amateur archaeologist Gustav Nordby told them of the many discoveries to be made in untouched settlement deposits. On St. John it was Reverend Penn who guided Gudmund Hatt to the island’s archaeological sites.

Archaeological methods

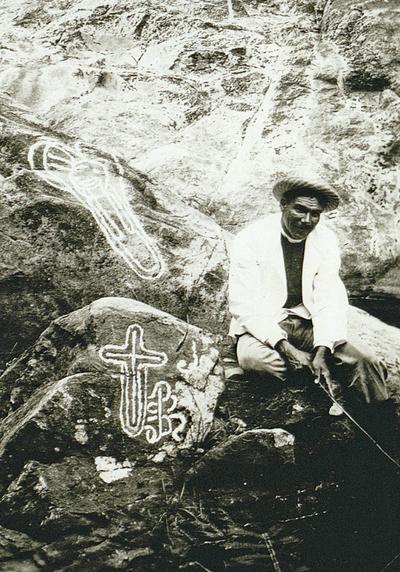

European and American archaeologists use very different methods. In American archaeology small test holes are usually dug to study the vertical layers of a site. In European archaeology the earth of a larger area is removed layer by layer to establish a more comprehensive horizontal overview. Gudmund Hatt was convinced of the advantages of the European method. By contemporary standards the expedition was incredibly well documented. Gudmund Hatt spent a lot of time describing, drawing and photographing his excavations, and today archaeologists still use his work when studying the pre-history of the Caribbean.

More than 20.000 objects

During the first excavations Gudmund Hatt collected almost every object he found. But transporting such large quantities of finds to Denmark became prohibitively expensive, so he tended to keep only the most interesting parts. He often broke the handles and decoration off pots, throwing the rest away. As a result there are hundreds of severed handles in Gudmund Hatt’s collection, and not many intact bowls and pots on the Virgin Islands. Was this a respectful way to treat the cultural heritage of others? We might not think so today, but it was not unusual during Gudmund Hatt’s lifetime.

The many excavations meant that by the end of the expedition Gudmund Hatt had sent approximately 22 m3 of archaeological material back to the National Museum in Denmark: around 4,600 registration numbers covering over 20,000 objects. The collection includes everything from axes and bowls, to large rocks with carvings. It also includes human skeletal material.

For almost a century this impressive collection gathered dust in storage at the National Museum of Denmark, without ever being the subject of serious study or an exhibition. In 2015, however, the museum digitalised, photographed and reanalysed the entire archaeological collection from the West Indies. To commemorate the centenary of the sale of the Danish West Indies to the U.S. in 1917 the digitised archive has now been launched online here.