Women in the Viking Age

The majority of women in the Viking period were housewives, who managed the housekeeping on the farm with a firm hand. It is also possible that there were female entrepreneurs, who worked in textile production in the towns.

Just like today, women in the Viking period sought a suitable partner. The sagas are filled with stories of women competing over who has the best man. However, love did not always last. So it was good that Scandinavia was a pioneering region when it came to equal opportunities. The Viking woman could choose a husband and later decide not to marry him after all, if she so wished. However, there were limits to the extent of these equal opportunities. For example, only men could appear in court in the Viking Age.

Housewives

The woman’s world was centred around the home and the farm. When the man was called on an expedition, the responsibility for the farm was handed over to the woman. From the moment the ship sailed out of the fjord it was her responsibility to secure the harvest and with this survival.

A woman’s work duties were, by all accounts, housekeeping and making food. A large part of her time was also taken up working wool, spinning yarn, sewing and weaving for the family’s own consumption. Pregnancy and breastfeeding also took up time in a woman’s life. In practice it was probably the women who looked after the children and elderly.

All members of the household, regardless of sex and age, probably helped with the daily tasks.

Female entrepreneurs

In the towns women worked with crafts. Archaeological finds show that the production of textiles was reserved for women, whilst metalwork and carpentry were undertaken by men.

Complicated production techniques indicate that certain women probably specialized in textile work. They may have participated in this trade for the sake of their families.

Equal opportunities in society

The written sources portray Viking women as independent and possessing rights. Compared to women elsewhere in the same period, Viking women had more freedom. However, there were limits to this. Even if women had a relatively strong position, they were officially inferior to men. They could not appear in court or receive a share of the man’s inheritance. It was the man who had the political power.

Marriage

The watershed in a Viking woman’s life was when she got married. Up until then she lived at home with her parents. In the sagas we can read that the woman “got married”, whilst a man “married”. But after they were married the husband and the wife “owned” each other.

There is believed to have been a hidden moral in the sagas in relation to a woman’s choice of husband. The family probably wanted to participate in the decision-making. When an attempt was made to woo a woman, the father did not need to ask his daughter’s opinion about the interested male. In cases in which the girl opposed the family’s wishes, the sagas describe how this often ended badly.

The woman’s reputation and place in society was connected to that of her husband. The sagas often describe how various women compete over who has the best husband. Young girls obviously knew what to look for in a prospective husband.

Divorce

If the marriage did not work, then the wife and husband could divorce. When the Spanish-Arabic traveller al-Tartushi visited Hedeby in the 900s he was surprised to hear that women had the right to divorce if they wished.

The sagas involve many divorced women and widows who marry again. The Icelandic sagas describe a large number of divorce rules, which are evidence of a quite advanced legal system.

The woman could, for example, demand a divorce if her husband settled in a new country whilst on his travels, but only if the man neglected to go to bed with her for three years. The aim of this was to secure the wife against a life of loneliness. The most typical grounds for divorce were, however, sudden poverty in the man’s family or violence on the part of the husband. If a man struck his wife three times she could demand a divorce.

Female infidelity was punished hard, whilst men were able to bring various mistresses into the home. However, the official housewife kept authority over the new women in the household.

We do not know how frequent divorces were in the Viking period, but the rights to divorce and inheritance indicate that women had an independent judicial status. After divorce, babies and small children generally went with their mothers, whilst older children were divided up amongst their parents’ families, depending upon their wealth and status.

Powerful women: queens and seeresses

The Icelandic sagas give examples of how a strong woman could overshadow her husband. It was a dangerous balancing act. Sometimes a wife’s drive and energy could make her husband respect her, whilst in other cases the man lost his reputation due to a powerful wife. The woman’s reputation, on the other hand, remained intact.

Women could achieve a great reputation and wealth. We can see this at the most magnificent burial of them all: the Oseberg burial in Norway. Here a woman aged around 25 was buried with an incredible array of equipment (see FACT BOX).

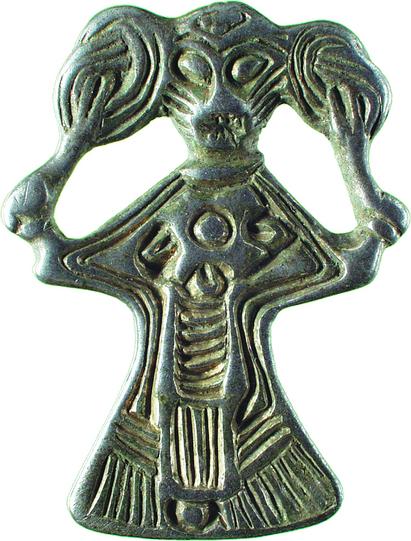

Women also played an important role in the pre-Christian cult. Seeresses were highly revered people. They could foretell the future, for instance, on individual farms or for army commanders before great battles.

The female burial from Oseberg

The richest burial of the Viking Age was found at Oseberg in Norway. Here a noble woman, perhaps a queen, was buried in a large ship.

Amongst the grave goods were many fine objects carved in wood. There were chests, buckets, beds, a chair, a carriage and sledges. She was also given bedding filled with fine feathers and down. Other grave goods included oil lamps, together with a tapestry displaying numerous fine patterns and figures. The woman had also been given large quantities of ordinary household utensils to accompany her in the grave. These included cooking pots, frying pans, buckets and knives.

The household items tell us about the woman’s role in society. Even if the women of the Viking Age could also achieve power like men, there were still some particular areas that they were responsible for: the home and the housekeeping.

Housewives as key carriers?

The literature tells us that all rich married Viking women carried keys amongst their personal items. The key symbolised the woman’s status as housewife. Or was this actually the case?

This view can at least partially be attributed to the keys that have been found in rich Viking women’s graves, as well as the legal texts, which state that the medieval housewife had the right to the keys of the house. However, archaeologists find increasing numbers of keys, but these are not necessarily from graves. This indicates that the distribution and use of keys was relatively extensive.

A closer examination of all female burials from the Viking period shows that keys found as grave goods are a rarity, rather than commonplace. Keys have only been found in c. 5 % of all women’s graves. Closer analyses show that keys are found in all types of burials, apart from those of the very wealthiest people. In addition, it should be noted that a number of the keys that have been found would not have been useable.

If the key cannot be interpreted as an expression of housewife status then what does it indicate? Keys can open and lock. If the meaning is transferred, then a key can also provide access from one phase to another, for example from childhood to adulthood. Should women with keys be seen as having special powers, which could be opened up and then locked away again, for example the power to see into the future? Therefore we should perhaps look upon women with keys as knowledgeable women rather than housewives.