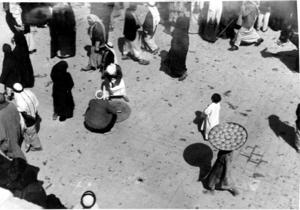

Hama in the 1930s

The Town

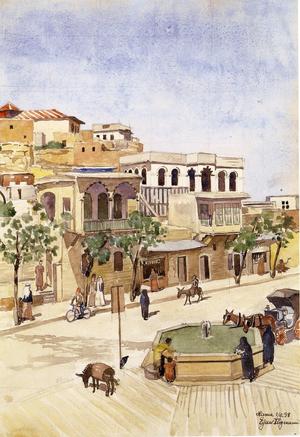

When the Danish expedition excavated the mound at Hama in the 1930s, the town at the foot of the mound remained relatively untouched by Western culture. It had been only a decade since Turkish Ottoman rule had been abolished, and even though the French colonial authorities had since then begun a slow modernization of the town, Hama in the 1930s remained to a large extent as it had been in the early Ottoman times.

Society was organized in a feudal fashion, with a few dominant clan lineages, which owned whole neighborhoods in the town and large properties in the environs. The wealthiest clans had a duty to help the disadvantaged in the town, and so the clan system functioned as a social and economic safety net for the most vulnerable citizens.

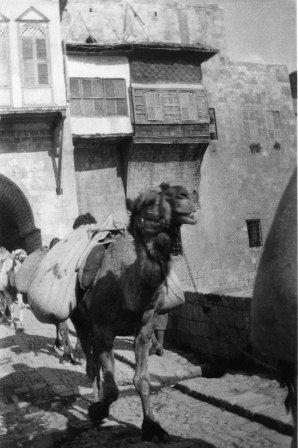

At that time there were few automobiles, and the town was served by only two trains a day. Movement was mainly on foot, horseback or donkeyback; camels were used for the transportation of bulky items.

Electricity was introduced at the beginning of the expedition, but initially only to the houses of the mayor and other city officials, military installations, and to the ‘Azm Palace. Other residents had to make do with candles and kerosene lamps.

Telephone calls could only be made in the suq (marketplace) or at the post office.

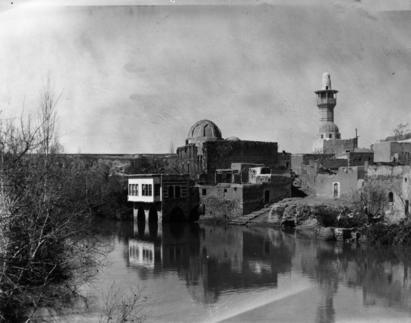

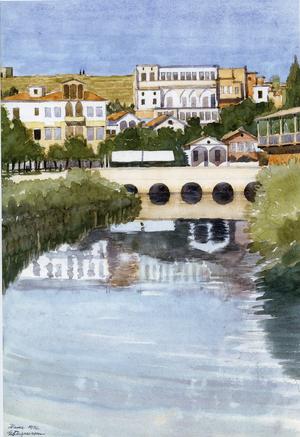

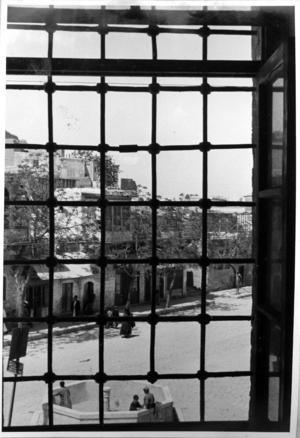

A characteristic noise heard throughout the town was the sound of the many waterwheels, which provided water to the town from the Orontes River. The water wheels brought the water up from the river into open aqueducts, which served the various quarters of the town.

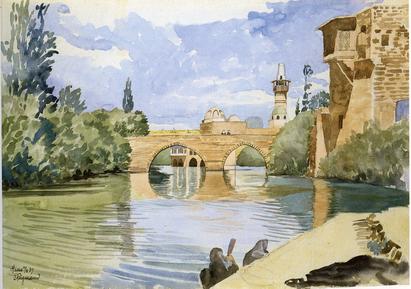

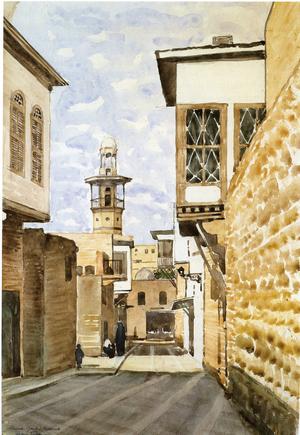

The river banks were often lined with women washing clothes, so that it could be difficult for the architect Ejnar Fugmann to find a place where he could paint his watercolours of the town.

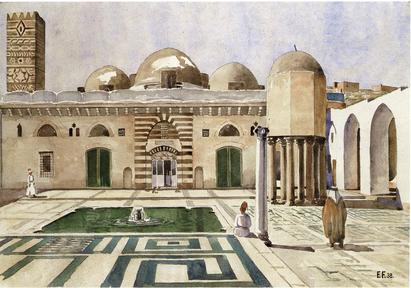

Historic Buildings

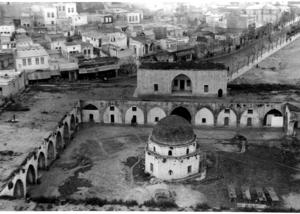

West of the mound lay the quarter known as Bab al-Qubli. A Roman temple had been built here around 250 CE, which had been replaced by a Christian church around 350-400 CE, and which, in turn, then became a mosque with the Arab conquest of Syria in 636 CE. During the Ummayad Caliphate (661-750), this building was enlarged to become “The Great Mosque” that stands today. Vestiges of both the Roman temple and the Christian church can still be seen within the mosque. The quarter around the mosque became an important religious center where buildings were continuously added and restored.

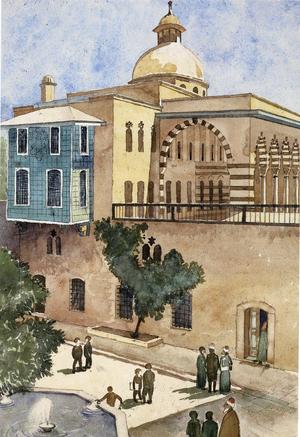

Many caravansarys (traveler’s inns) were also located in the town; Khan Rustam Pasha, built in 1561, served as the expedition dighouse. Khan Rustam Pasha lay in the Dibbagha quarter, which was the more modern part of the town. Here was also located one of the few hotels in the town, with a small café in front.

The ‘Azm Palace was built by the Ottoman governor as his residence in 1742. Considered one of the most beautiful Ottoman Period buildings in Syria, today it serves as an archaeological museum.

If you want to learn more about the various buildings of Hama, see Fugmann's watercolour.

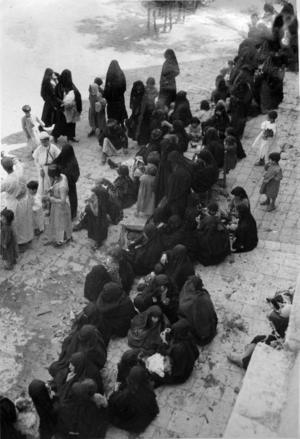

The Population

Around 50,000 people lived in Hama in the 1930s. Christians, who made up 20% of the population, lived in the al-Madina (“the city”) quarter, the oldest neighborhood in the town.

Most inhabitants wore traditional Near Eastern garb; some members of the elite wore Western suits, along with the Ottoman fez hat. Most women wore veils that covered their face, neck and shoulders, or more voluminous robes that covered their whole bodies.

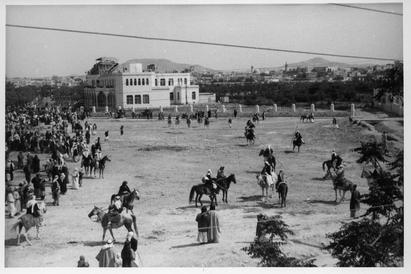

Commerce and Horses

Commerce was concentrated on textiles and leather goods, which were mostly sold to the Bedouins from the neighboring desert regions. Hama was also known as the best market for horses in all of Syria. Horse races and other contests were held during the Eid al-Kabir Festival. Purebred Arabian horses were bred by the Bedouin, who considered them a gift from Allah. These famous horses thrived in dry, hot conditions, and Syria had a long and proud tradition of breeding Arabian horses. Horse competitions have continued to be held in Hama during festivals (most recently in 2010), where the most beautiful horse is chosen by knowledgeable horse lovers.